An emerging trend in EPFO's debt investments

Every investment category but one has seen a drop in its share: it's a move that is not without some risk.

India’s Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation (EPFO) is changing its investment mix, prioritising state debt as it manages social security accounts of 258.8 million members.

EPFO’s share of state development loans (SDLs)--used to bridge the gap between a state government’s spending and income--has gone up by 16.03 percentage points since 2016-17. The share of such loans in the total debt corpus, based on face value, was 26.39 per cent in 2016-17. It has increased to 42.42 per cent, according to data for 2020-21—the latest date for which information is available.

Investments in every other major category have dropped. EPFO’s share of central government securities is down 4.75 percentage points; the special deposit scheme share has fallen 2.58 per cent. The sharpest fall is in the money allocated to public sector financial institutions, public sector undertakings, and private sector bonds and securities. These have collectively seen a drop of 7.59 percentage points in the EPFO’s debt portfolio as seen in chart 1 (click image for interactive link).

EPFO’s debt investments are worth Rs 14.46 trillion and equity investments, where exposure is relatively recent, are worth Rs 1.23 trillion.

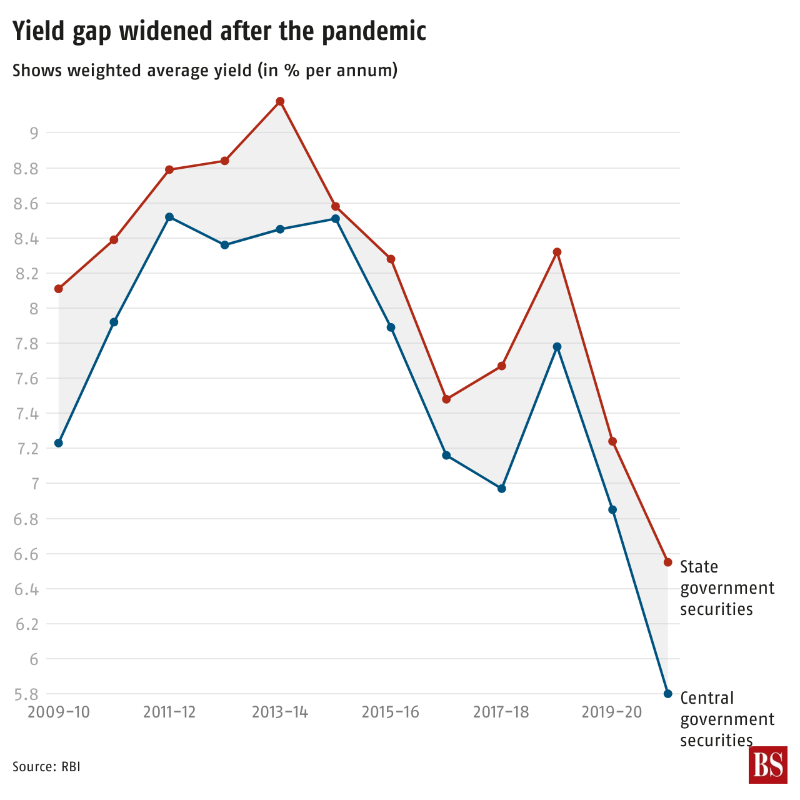

The surge in state government paper comes as the gap widens between what subscribers get as returns for their money parked with EPFO and what the organisation can expect from debt markets—the yield on central government securities being one example. The gap between returns on 10-year central government securities and EPFO’s promised return to subscribers grew to its widest in almost a decade in 2020-21. State government securities typically offer higher interest rates. The difference between state and central government yields was at its highest in 11 years as of 2020-21 (see chart 2).

The EPFO announced on March 12 that it would give its members 8.1 per cent interest on their holdings for 2021-22. This can be a challenging target because of relatively low interest rates on debt and volatility in equity markets. Higher allocations to state government debt poses its own challenges: poorer liquidity compared to central government bonds and a sense that yields may not fully reflect inherent risks.

The yield on a state government paper may not always fully reflect on a state’s ability to pay back the money.

“…the existing empirical literature in the Indian context finds a weak association between SDL yield spreads and fiscal metrics, suggesting the lack of perceived risk by investors across Indian states in the market borrowings space,” said a January 21, 2022 Reserve Bank of India research paper entitled ‘States’ Fiscal Performance and Yield Spreads on Market Borrowings in India’.

It is not inconceivable that higher borrowings and increased market scrutiny could change risk perceptions for individual states. Indeed, there is a wide difference in the shortfall between what various state governments earn and what they spend, relative to the size of their economies (see chart 3).

“The high committed expenditure, particularly on interest payments, has a tendency of a vicious cycle whereby lesser resources could be made available for productive expenditure, which in turn could adversely affect GSDP (Gross State Domestic Product) growth and revenue mobilisation. Investors could have a low preference for states with high committed expenditure and may demand higher yield spreads,” said the RBI paper authored by Ramesh Jangili, N R V M K. Rajendra Kumar and Jai Chander.

The chance of a state government defaulting is remote, but greater transparency could help in anticipating risks for a long-term investor like the EPFO. Details on individual state exposure are not available. Individual private sector exposure is unavailable as well.

EPFO did not reply to an email Business Standard sent it for its comment.