As private universities expand, a question of caste and representation

Institutes in South India do better in including OBC students, but nationwide SC, ST and OBC communities don’t have a fair share

As private universities expand in India’s higher education system, questions about what access they give to historically marginalised communities have gained attention. These institutes often benefit from public support such as land grants, tax exemptions, and regulatory flexibility, but they are not obliged to follow the affirmative action mandates governing public universities.

This has implications for students of Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST), and Other Backward Classes (OBC), who already face significant structural disadvantages in accessing quality education. April 14 is Ambedkar Jayanti, a day commemorating the architect of the Indian Constitution and advocate for social justice, and an opportune moment to examine the representation of these communities in private higher education.

An analysis of the share of SC, ST, and OBC students among the total student population in private universities reveals significant regional disparities. A sharp difference emerges in the representation of OBC students. They comprise 46 per cent of all students of private universities in South India, suggesting a significantly more inclusive environment, at least for this group. Private universities in North India reported a mere 6.3 per cent OBC enrollment, according to a report by the Parliamentary Standing Committee on education, women, children, youth and sports presented before the Rajya Sabha on March 26.

South India, with its history of implementing social justice policies and caste-based movements, appears to have cultivated more robust participation of OBC communities in higher education.

North India is slightly ahead of the South in SC and ST students’ representation in private universities: 6 per cent and 1.6 per cent compared to 3.7 per cent and 0.6 per cent but the share is modest in both regions (chart 1, click image for interactive link).

The committee’s report showed that Birla Institute of Technology and Science, Pilani, one of India’s leading private universities, had no students from the SC, ST, or OBC categories in 2022-23.

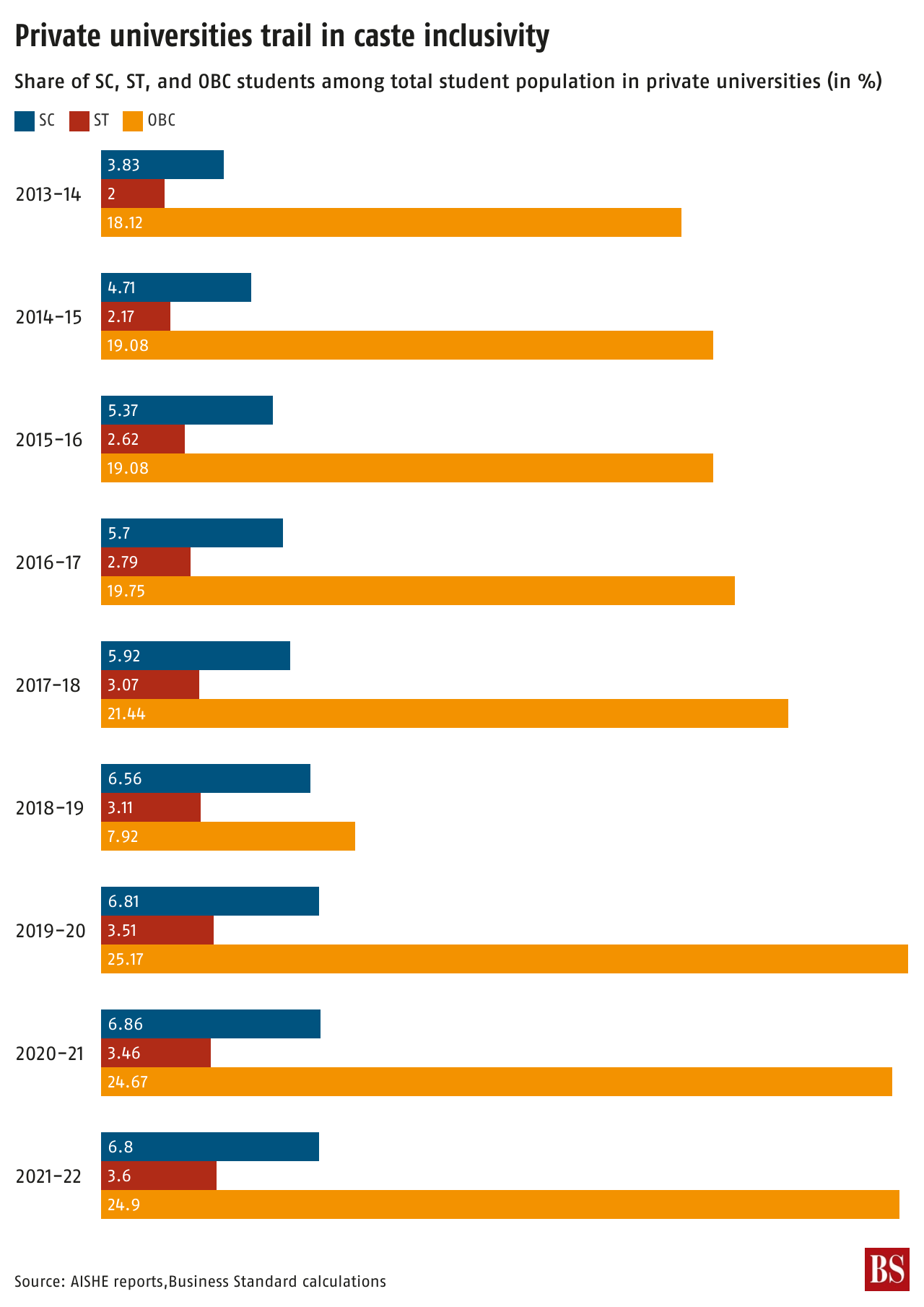

Representation of SC, ST, and OBC students in private universities nationwide from 2013-14 to 2021-22 improved modestly, according to data in All India Survey on Higher Education (AISHE) reports. SC students’ enrollment rose from 3.83 per cent in 2013-14 to 6.8 per cent in 2021-22, a gain of just under 3 percentage points over nearly a decade. ST students’ representation increased from 2 per cent to 3.6 per cent.

OBC students’ representation was somewhat more dynamic but still worrying. Starting at 18.12 per cent in 2013-14, their share grew steadily, peaking at 25.17 per cent in 2019-20. The share then declined and settled at 24.9 per cent in 2021-22 (chart 2).

The underrepresentation of marginalised communities becomes stark when examined in the light of the rapid growth of private higher education institutions. Between 2015 and 2024, the number of private universities (including deemed universities) increased from 276 to 523, marking a near 90 per cent rise in less than a decade. As of 2021-22, private universities accounted for 26 per cent of total higher education enrollment in the country. Private unaided colleges account for about 45 per cent of total student enrollment.

The representation of marginalised communities in the teaching staff in private universities is even more limited. According to an analysis of the Parliament committee’s report, only 4.1 per cent of faculty members in top private universities belong to SC communities. OBCs account for about 30 per cent of faculty.

The report had data on 34 private universities featured in the National Institutional Ranking Framework's top 100 overall rankings, detailing enrolment and faculty distribution across different social categories.

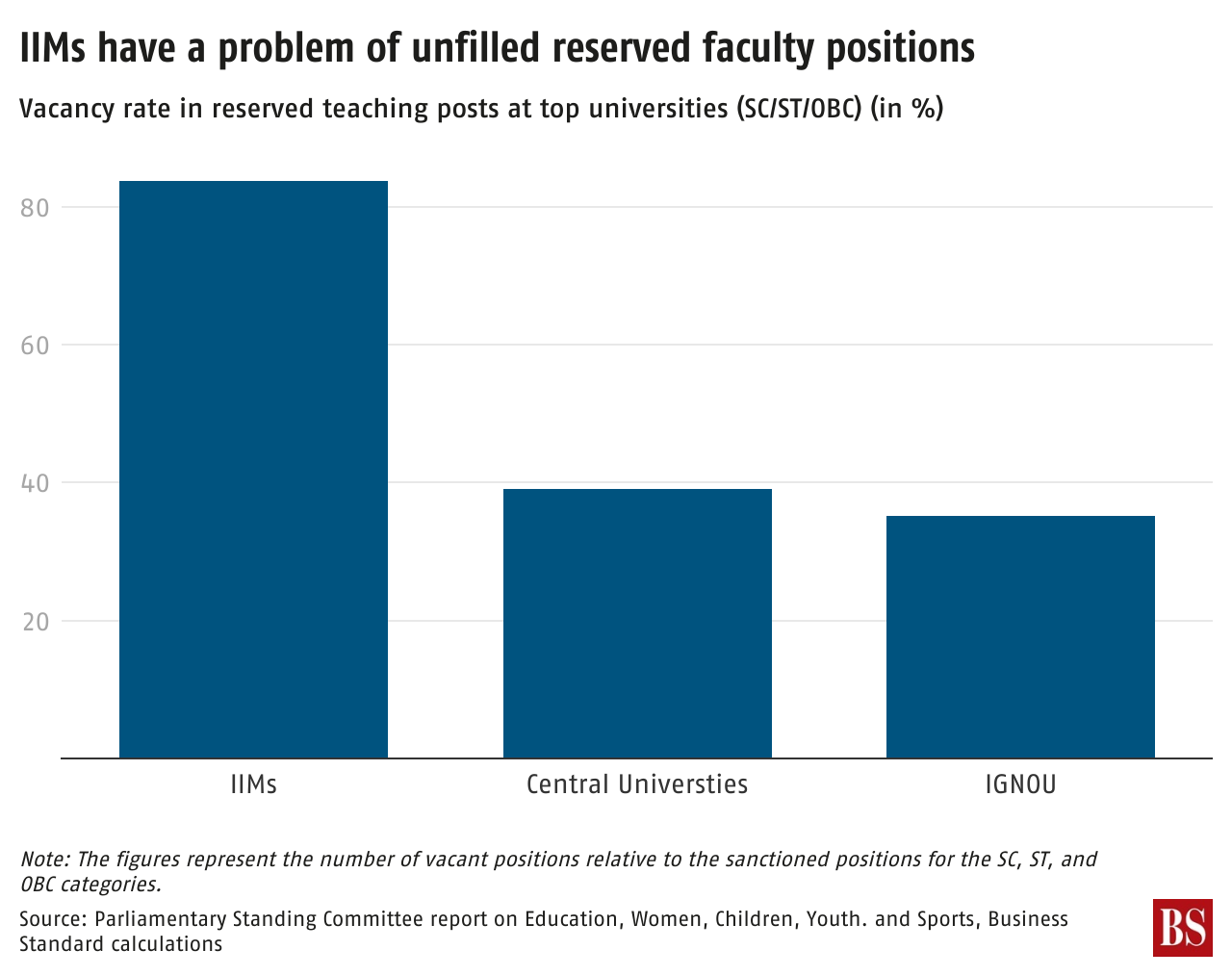

State-funded institutions are legally mandated to follow reservation policies but they are often lax. Data in the same report shows that 83.7 of reserved teaching positions for SC, ST, and OBC categories in the Indian Institutes of Management are vacant. Central universities fare only slightly better, with 39.1 per cent of such positions unfilled (chart 3).