India is saving without gaining

Households are putting their money in investments that don’t help the government in building a social safety net

One of the first things you learn from an introductory macroeconomics text is that saving needs to be equal to investment for economic equilibrium. This Keynesian equality has become a widely accepted economic rule. Although the relationship is not as simple as the S=I equation, it has withstood the test of time.

In India, savings are declining. The latest annual report of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) showed that gross savings fell in 2020-21 to 27.8 per cent of the gross national disposable income (GNDI). In 2017-18, it was 31.7 per cent of the GNDI.

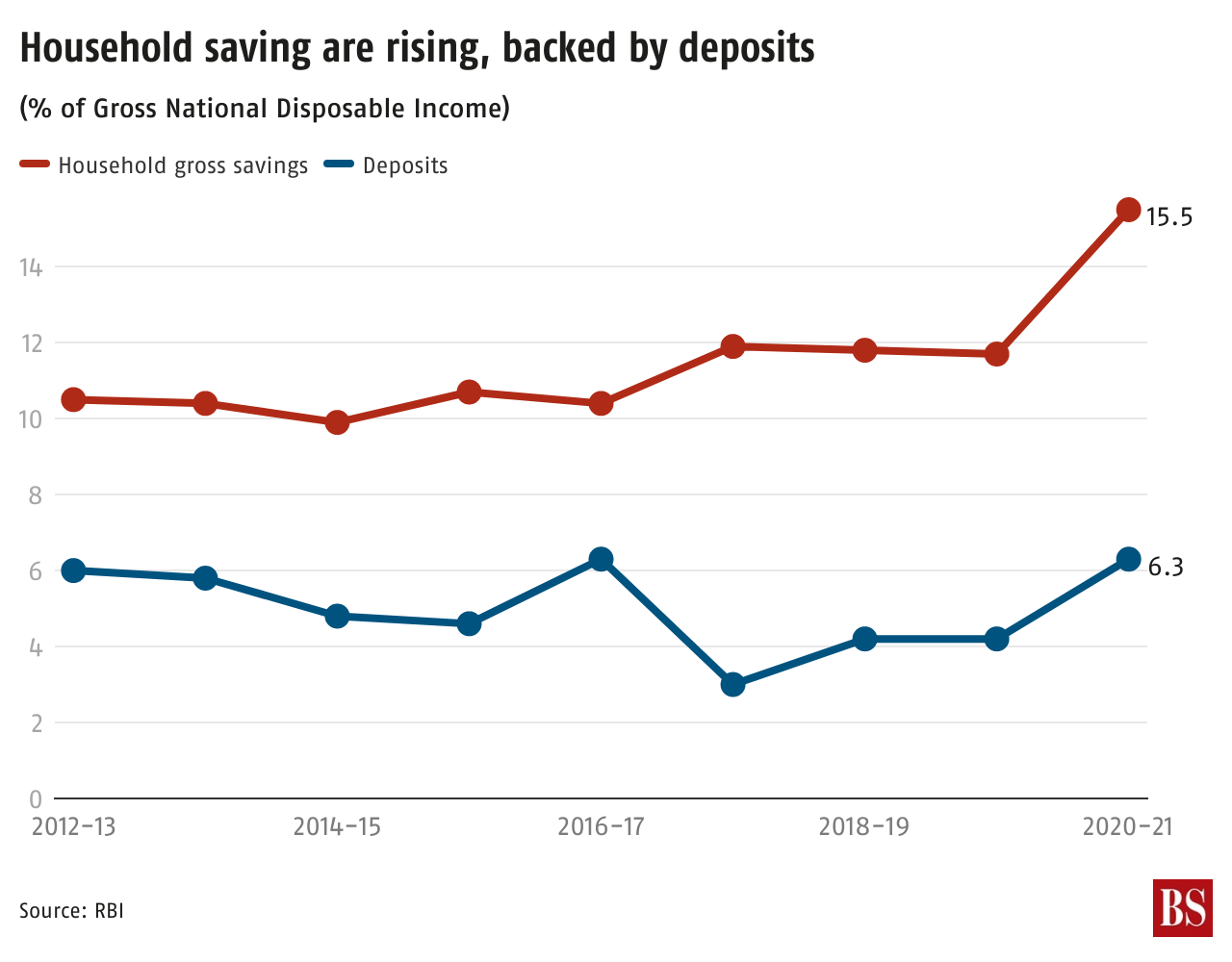

The problem is with households. RBI data shows that though gross household savings as a proportion of GNDI rose 3.8 percentage points in 2020-21, it is not the kind of number India wants. Household financial savings rose to 15.5 per cent in 2020-21--the highest in two decades--but the surge can be attributed to a 50 per cent increase in deposits compared to the previous year. As a proportion of GNDI, deposits rose from 4.2 per cent in 2019-20 to 6.3 per cent in 2020-21. The coronavirus pandemic and lack of consumption activity forced people to do precautionary savings. The trend is also evident from rise in currency in circulation.

Revenge buying as coronavirus cases fell would have eroded this. RBI data shows the pandemic did not change the appetite for pension and market products. It indicates that investment in shares and debentures rose just 0.1 percentage points from 0.4 to 0.5 per cent of GNDI in 2020-21. Savings in provident and pension funds was a meagre 2.5 per cent in 2020-21, compared to 2.2 per cent in 2019-20. Savings in insurance products rose from 1.8 to 2.6 per cent during this period. One also needs to consider that the quantum of actual saving may be lower, as incomes declined in 2020-21 due to disruptions caused by the pandemic and ensuing lockdown.

The failure to create a pensionable society is evident from the response to pension products, especially at the bottom of the social pyramid. Consider the performance of the government’s flagship Atal Pension Yojana. By January 2022, the government said that 36.8 million people had subscribed to Atal Pension Yojana. In contrast, 277 million people have registered on e-shram portal to avail of government benefits, and there are an even greater 500 million people in the unorganised sector. Even those in the organised sector do not have adequate pension coverage.

More people will require a safety net as the country witnesses a demographic shift and has a huge elderly population. If the government can’t create a pensionable society, its subsidy bill will balloon.

India needs the other kind of saving now.